Goals for revenue growth change over the lifecycle of a company, in both magnitude and composition: Early stage startups want 100 percent growth or more. Late stage startups aim for 60 to 80 percent growth. Companies near the public offering stage are in the 40 percent range. For public companies, growth objectives start to fall below 20 percent.

As companies mature, growth begins to blend new customer acquisition with existing customer upgrade and add-on sales—and for the best-performing companies, an increasing percentage of growth comes from existing customers, year over year. In fact, for these best-performing companies, our research shows a direct correlation between average customer lifetime and percentage growth contribution from existing customers.

To better understand this dynamic, consider the following example: A late stage startup plans to grow 60 percent, from $40M to approximately $64M in annual recurring revenue (ARR). To achieve this growth, the company plans to secure $37.6M in renewals (i.e., a 94% renewal rate), $3.9M from upgrade sales, $3.9M from add-on sales, and $18.6M from new customer acquisition.

Their model amounts to $26.4M in new ARR to achieve this 60 percent growth, with $7.8M of that coming from existing customers—which means that existing customers are contributing 29.5 percent of the growth. While every company will have their own unique dynamics, this basic model applies—and as average customer lifetime increases for a company, so too will the potential for upgrade and add-on sales in the growing customer base.

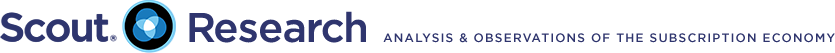

So what correlations did we find between growth, average customer lifetime, and percentage contribution from existing customers? The table to the right summarizes our findings with these best-performing companies.

In short, companies growing at 80 percent or more had average customer lifetimes of less than two years and derived less than 20 percent of growth from existing customers. For companies growing in the 40 to 80 percent range, average customer lifetimes were two to three years and sometimes four. These companies derived anywhere from 20 to 40 percent of growth from existin g customers. When growth rates dropped below 15 percent, companies had average customer lifetimes greater than four years and the majority of growth came from existing customers through upgrade and add-on sales. The table to the right summarizes these findings.

g customers. When growth rates dropped below 15 percent, companies had average customer lifetimes greater than four years and the majority of growth came from existing customers through upgrade and add-on sales. The table to the right summarizes these findings.

The Implication

Maximizing customer lifetime is not a revenue-retention strategy. It is a revenue-growth strategy. More importantly, maximizing customer lifetime is a strategy for sustainable revenue growth—but it’s a strategy that requires a deep understanding of how customers use your products and services.

In the subscription economy, customers are migrating from pay-to-own to pay-to-use. A growth strategy requires product lines and rate plans that are designed for upgrade and add-on sales based on usage. That is, products should be designed to have logical, complementary functionality, and rate plans should be tiered to match usage patterns. Product management needs to study and understand actual customer usage data and then iterate pricing and packaging to align products and rate plans to customers’ needs by demographic.

Equally important, a company’s account management strategy needs to be based on adoption processes that create customer value and proactive engagement points—so you can make the right offer at the right time to each individual customer. An account management strategy that does not address both customer success and sales requirements will fall short in driving growth. To execute a well-designed account management strategy, you need transparency of customer usage.